Why Autism Often Unveils the Rare Savant's Syndrome Connection

Even though a first known account of the perplexing condition appeared in a journal in 1783, what savant syndrome is … and isn’t … remains an enigma in terms of what causes it and why it has a strong association with autism spectrum disorder.

A good savant’s syndrome example is the character Raymond (played by Dustin Hoffman) from the movie Rain Man. Raymond is an autistic savant with exceptional memory and math skills, but is incompetent when it comes to money. In fact, he doesn’t even understand the concept of money. Many savants in real life can be the same way, which is why some need so much attention and care

While the portrayal of autism is controversial ( you can read what I wrote about the movie here), the 1988 film does give a decent example of autism savants.

Common characteristics of savant’s syndrome is that they can be phenomenal at a specific area, but not overall. Savants and autism skills that co-occur are linked to domains of ability and talent that far exceed what is considered normal. These skills are rare overall, but research suggests they may occur more frequently in some populations, like those with ASD.

RELATED: Exploring Myths and Realities of High Functioning Autism Symptoms

Defining Autism Savants and Their Skills

Individuals with both autism and savants traits share areas where an individual demonstrates abilities that are far above average. These skills stand out in contrast to the person’s overall developmental, cognitive, and adaptive abilities. There is no standard IQ cutoff for savants, but their exceptional talent will be markedly above their general level of functioning.

Savant skills tend to cluster around five areas:

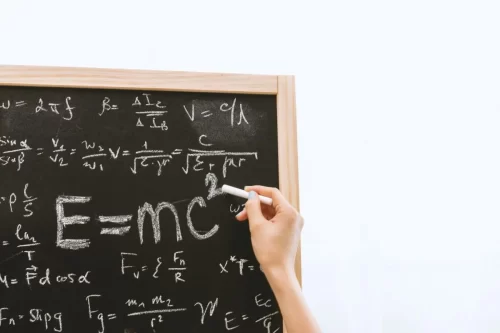

- Math abilities: calculating calendar dates, prime numbers, or complex computations far beyond expectations

- Memory: exceptionally strong memorization for details, dates, faces, facts, or trivia

- Artistic abilities: advanced graphic abilities, attention to detail, spatial skills in drawing or sculpture

- Musical abilities: ability to replay complex musical pieces after one listen or identify tone pitches and instruments

- Spatial skills: advanced understanding of measurement, directionality, geometry

Though thresholds vary, truly prodigious savants possess skills in the top 1% or .1% compared to population norms and expectations. Additionally, savant skills tend to be associated with intense fascination, concentration, and devotion within skill areas from very early in life. However, it’s important to note that savantism and its abilities can come and go suddenly.

RELATED: Do You Know Your Flavor of Autism Spectrum Disorders?

Autism and Savants: Connections Between The Two

Savant skills have been documented in various developmental and neurological conditions. However, they tend to co-occur most prominently with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It is estimated that up to 10-30% of autistic individuals possess savant abilities in contrast to less than 1% of the non-autistic population.

At the same time, there are no definitive statistics about how many individuals truly possess savants syndrome abilities, or how many have the co-occurring conditions of having both autism and savants syndrome. But why might savant talents emerge more frequently among those with autism?

Research points toward neurobiological factors associated with autism that may unlock latent savant potential. Studies using MRI scans have found that autistic savants tend to show enhanced local connectivity combined with reduced long-range connectivity. This means stronger connections within brain regions associated with the savant skill area, but less coordination between widely separated brain regions.

One theory suggests that this pattern of connectivity deficiencies combined with functional strengths allows concentrated neural circuits to become highly specialized in certain tasks.

Additionally, some researchers propose a failure of top-down inhibition may unleash skills that would normally be suppressed or fail to fully emerge. Commonly developing individuals learn to suppress the intense focus on details that is displayed by young children in order to process higher-order patterns.

In autistic savants, however, failures in synaptic pruning or connectivity may result in a retained and undisrupted channel for detail-oriented thinking. Unchecked by inhibitions, these intense interests are then fueled into specialized talents.

Together, enhanced local connectivity and insufficient top-down control provide conditions suitable for savant skills to manifest. And in fact, studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) have shown that interrupting activity in the front part of the brain leads temporarily enhances savant-like skills even among non-autistics.

This lends support to the theory that savants have privileged access to raw, unfiltered forms of information processing.

There’s also the theory that severe head trauma or brain injury in left hemisphere of brain leads to the compensation in the right hemisphere and can result in extraordinary specific skills.

Spotlight on the Spectrum: Understanding the 3 Levels of Autism

Savant’s Syndrome Myths and Realities in the Autistic Genius Stereotype

This myth stems from an overgeneralization: because rates of savantism are significantly higher in autism compared to the general population, observers mistakenly assume savant abilities characterize all or most autistic individuals.

In reality, the majority of individuals on the spectrum show average or even impaired cognitive capacities across many domains commonly associated with savant talents. Challenges are not limited to savant domains either – deficits in adaptive functioning, independent living skills, and communication abilities are hallmarks of autism that affect a majority on the spectrum.

This myth can be damaging because it glosses over the support needs of lower-functioning individuals, overlooking barriers to independence faced by many autistics. When combined talents of autism and savants are expected, lack of special skills can discount other strengths and lead to inadequate support provision.

The autism savants stereotype also makes invisible diverse voices of average-ability autistic self-advocates. As the neurodiversity movement demonstrates, gifts can manifest in many forms like high empathy, novel problem-solving perspectives, and intense passions—no savant skills required!

In addition, savant disorder isn’t a thing, as savants syndrome isn’t classified as a disorder. This means that criteria to define what “it is” doesn’t exist.

Debunking the savant disorder stereotype is key for empowering inclusive communities. Embracing neurodiversity means recognizing a wide spectrum of strengths and challenges beyond singular skill subsets. Appreciating this complexity fosters opportunities for more autistic individuals to have their talents, support needs, and perspectives recognized and valued.

Autism and Savants: Are They Born or Made?

Another question surrounding autism savants is whether their skills are innate talents, or the result of intense practice and concentration? Like most complex traits, savant abilities likely emerge from a combination of inherited gifts and environmental cultivation.

Many savants demonstrate predisposing characteristics and precocious interests from a very early age—suggesting a biologically-based affinity. For example, prodigious savant artists may display innate hyper-visual sensitivities, while musical savant sensitivities tune into the nuances of pitch and tone. Heightened development in these domains point to early emerging propensities.

However, most experts agree that natural inclination is not sufficient alone—savant skills are honed over time through intense practice and devotion, if they even stay around.

Even child prodigies log countless hours immersed in their field from very early ages. neural hyperconnectivity within skill circuits likely facilitate rapid acquisition and acceleration. But continuous exposure, focus, and challenge still play pivotal roles in developing high-level savant abilities or a type of savant disorder classification.

This combination of innate talent and cultivated mastery mirrors expertise acquisition in other specialized domains like chess, sports, or computer coding. Hard work fuels growth, but some underlying aptitudes ease the path.

This underscores why late-emerging savants are more rare: though the intrinsic potential existed, it was not nurtured or revealed until some change unlocked access.

RELATED: Autism on the Brain: Unpacking the Meaning Behind Neurodiversity

Late-Emerging Savant’s Syndrome Individuals: Challenging Innate Explanations

While many savants exhibit remarkable, early talent, some cases defy the narrative of rigidly innate skills. Some individuals develop savant-like skills spontaneously, later in life, resulting from illness, injury, or other intervening events.

For example, following a left-brain stroke, patient Tommy McHugh suddenly developed art and poetry talents he did not possess previously. Orlando Serrell gained calendrical and numerical recall abilities after being struck by a baseball at age 10. And following frontotemporal dementia, Bruce Miller’s patient developed a passion and flair for painting without any prior art background.

These cases demonstrate that the intrinsic potential for specialized skills may lie dormant in more people, unlocked under certain neurological conditions. Some researchers argue this lends credence to theories that savant skills represent normally suppressed pathways of thinking that are suddenly revealed. Resulting hyperconnectivity in new regions, combined with diminished inhibition, allows sudden savant talents to emerge unexpectedly.

Studies of induced savantism provide further support that specialized abilities may be latently buried, awaiting liberations.

Neuroscientist Allan Snyder uses low-frequency magnetic pulses to temporarily dampen activity in the left anterior temporal lobe. Right afterward, test subjects demonstrate enhanced proofreading, drawing, and memory capacities reminiscent of savants. While not fully replicating savant proficiency levels, these induced changes reveal flashes of ability, hinting at untapped potentials within everyone.

Such findings caution overly innate assumptions, demonstrating the brain’s latent capabilities when inhibitory constraints shift. Savant disorder skills likely involve a complex interplay between preexisting neural traits and environmental nurturing (or interrupting) of these pathways. While propensities may differ, specialized talents ultimately reflect both Nature and Nurture.

The Promise and Perils of Savant Skill Training

However, attempts to directly “train” savant skills have had mixed outcomes thus far.

Some small studies have attempted to replicate Snyder’s magnetic stimulation interventions with non-autistic adults to enhance cognitive functions like proofreading or drawing. Results reveal temporary bursts of ability reminiscent of savants – with detail-oriented and creative skills showing transient improvements. However, it remains unclear whether longer-term training could induce lasting savant-like proficiency.

Other approaches have focused directly on developing skills through programs tailored to autistics with potential talents. For example, Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences theory informed a school focused on encouraging savant abilities. Students pursued intense training related to skills like math, art, or music based on their profile. Some individuals supposedly did demonstrate savant-level proficiency following this cultivation of intrinsic strengths.

However, debates continue regarding the ethics of deliberately enhancing talents along some dimensions while other skills lag behind. Autism advocates argue forcing skill development in narrow domains ignores individual agency and self-determination.

Without consent, intensive training regimes could prove burdensome, especially for autistics who thrive through balancing skill-building with rest and relaxation needs.

Additionally, focusing singularly on enhancing splinter skills promotes an unbalanced developmental trajectory. Some worry pushing exceptional talent in savant domains risks glossing over crucial life skills, communication abilities, and holistic wellbeing. Hence, skill-training programs warrant balanced implementation to empower those with high potential without discounting support needs.

While savant skill training may show promise to some researchers, interventions require judicious structure to avoid overemphasizing singular talents at the expense of individual empowerment.

Skills development unchecked by person-centered supports risks promoting “performance savants” for applause rather than fulfillment. Harnessing potential must honor agency and diversity of strengths while underscoring that no one path defines success across the spectra of minds.

RELATED: History of Autism – Revealing Shocking Mysteries from the Past

The Future of Savant’s Syndrome Research

Much remains unknown regarding the precise neurological underpinnings of savant abilities and how potentials vs. savant disorder considerations might be cultivated ethically. However, savant skills provide a unique window into atypical cognitive processing, highlighting alternate modes of thriving.

Ongoing research is unraveling the complex interplay between predisposing traits, neural connectivity patterns, and environmental nurturing underlying savant development. Emerging studies are also explaining mechanisms like left-brain inhibition that temporarily enhance specialized skills, possibly hinting at untapped potentials within us all and not just for savants and autism connections.

As neurodiverse empowerment movements emphasize, cognitive variability is best framed as spectrums rather than binaries. Savants showcase extremes of ability, but signs and symptoms like splinter skills, talented savants, and prodigious savants exist across populations and minds.

Harnessing lessons from savant research may peek at insight into undeveloped potentials achievable when we embrace and support diverse minds.

Harnessing the Potential in All Minds and Not Just Autism Savants

Seeing savant abilities through the lens of neurodiversity further cautions binary “disabled vs gifted” stereotypes, highlighting interventions that unlock potentials.

Some argue that cases of induced savantism suggest that anyone has specialized skills “in there somewhere.” Evidence hints that left-brain dampening reduces top-down inhibition, unleashing detail-oriented processing capacities suppressed in most mature minds.

While savant proficiency levels remain extremely rare over the population, evidence hints that differences are quantitative rather than categorical.

Understanding neurological conditions associated with savantism may one day help structure interventions that harnessing splintered skills opportunities exist across the spectrum of minds—seen clearly in both autistic and neurotypical populations under certain conditions.

Ultimately, savant research highlights untapped cognitive potentials within us all. Appreciating rather than pathologizing alternate mind states opens possibilities to better leverage specialized abilities that enable human flourishing.

Though an extremely small minority, autistic savant perspectives serve as trailblazers toward more inclusively empowering the exceptional gifts embodied in every brain.

Additional Misconceptions That Lead To Autism Stigmas and Stereotypes

- Learn more about other stigmas and stereotypes that autistics face:

- Why Labeling People Can Lead to Stereotyping and Discrimination

- Autism Media Stereotypes: We’re Not All Geniuses, Savants, or Lonely

- Beyond Stereotypes: How Rain Man Revolutionized the Perception of Autism

- Absurd Plot About Autism and Evolution and Why It’s Harmful

- Moving Past the Tired Conspiracy Theory of Vaccines and Autism

- Discover the Powerful Bond Between Autism and Pets

- Reasons Why Pathologizing Crushes Autism Acceptance and Inclusion

- The Hidden Hurdles: Challenging Autism Stigmas in Today’s Politics

- History of Autism: Revealing Shocking Mysteries from the Past