Understanding Autistic Rumination: When Thoughts Circle Back

This is why smart people tend to end up in undesirable scenarios, because when you have an overactive brain you can rationalize any unsmart, impractical, or even ridiculous decision. I’ve been guilty of this and it gave me some pretty serious anxiety even though I could’ve easily avoided the whole thing!

This is why I want to warn you about how dangerous overthinking can be. Underthinking is also harmful as well, but overthinking is arguably worse because it allows you to create problems out of thin air. I had suffered through this a lot during high school and let me tell you it is exhausting!

By the time you can get your repetitive behaviors out of your system all your energy will have left too and you’ll be left drained both physically and emotionally. This is why it’s so important to find and develop healthier coping mechanisms that’ll leave you stronger, not weaker. I know life can be exhausting but there are better ways to take care of yourself; you just need the patience and self-love to embrace these new methods.

For many autistic people, the mind can feel like a record player with a scratched groove—the needle catches on the same spot, playing the same sequence over and over. This is rumination, and while it’s something many people experience, it often manifests differently and more intensely in autistic individuals.

What Is Autistic Rumination?

Rumination is the repetitive focus on thoughts, feelings, or experiences. For autistic people, this might involve replaying social interactions dozens of times, analyzing every word and gesture, or getting stuck on a problem that refuses to resolve itself. It’s not simply “overthinking”—it’s a cognitive pattern that can feel impossible to interrupt, even when you recognize it’s happening.

The autistic brain often processes information differently, with a tendency toward detail-focused thinking and pattern recognition. These same strengths can become vulnerabilities when the mind latches onto distressing thoughts or unresolved situations. While neurotypical individuals might be able to dismiss an awkward moment with a mental shrug, the autistic mind may continue analyzing it, searching for understanding, patterns, and meaning long after the moment has passed.

This isn’t a conscious choice. You can’t simply decide to stop ruminating any more than you can decide to stop being hungry. The thoughts arrive unbidden, often at inconvenient times—while you’re trying to fall asleep, in the middle of an important task, or during moments when you’re trying to relax and recharge.

Common Triggers and Themes

Autistic rumination frequently centers around specific areas that reflect both the challenges and characteristics of autistic cognition.

These social replays can be exhausting. You might find yourself mentally rehearsing what you should have said, analyzing whether you came across as too intense or not engaged enough, or trying to decode ambiguous facial expressions and voice tones. Each replay might reveal new details to worry about, creating an expanding web of concerns rather than resolution.

What makes this particularly challenging is that social communication is often genuinely ambiguous. Neurotypical people rely on intuition to navigate this ambiguity, making rapid unconscious assessments about meaning and intent.

Autistic individuals often try to consciously analyze what others process automatically, and when the data doesn’t yield clear answers, the mind keeps searching.

Sensory experiences can also become objects of persistent focus. An uncomfortable texture, an unexpected loud noise, or a disrupted routine might replay mentally long after the physical experience has ended.

The sensory sensitivity that many autistic people experience doesn’t end when the stimulus disappears. The memory of the sensation can feel almost as vivid as the original experience, and the mind may repeatedly return to it, trying to process or prepare for future encounters.

Justice and fairness issues often trigger intense rumination. Many autistic people have a strong sense of right and wrong, and witnessing or experiencing injustice can create a loop of thoughts about what should have been done differently, what might still be done, or why the situation happened at all. This might involve workplace dynamics, social situations, news events, or personal experiences. The rumination can include detailed mental arguments, imagined confrontations, or elaborate plans for addressing the injustice—even when taking action isn’t possible or practical.

Unfinished tasks or unresolved problems can create mental loops that interfere with sleep, work, and daily functioning. The autistic preference for completion and certainty means that ambiguity can be particularly distressing. A project that’s 95% complete might generate more mental distress than one that’s barely started, because the mind knows exactly what remains undone and can’t let go of it.

Past mistakes or embarrassing moments may be replayed with cinema-quality detail, sometimes years after they occurred. These memories can feel as fresh and distressing as if they happened yesterday, complete with the emotional intensity of the original experience. The autistic tendency toward vivid, detailed memory can make these recollections particularly painful.

The Burnout Connection

Autistic rumination often intensifies during or after periods of burnout. When executive function is depleted from masking, sensory overload, or navigating a neurotypical world, the ability to redirect thoughts diminishes. The mental resources that might normally help you shift attention or regulate emotions are exhausted, leaving you vulnerable to getting stuck in thought loops.

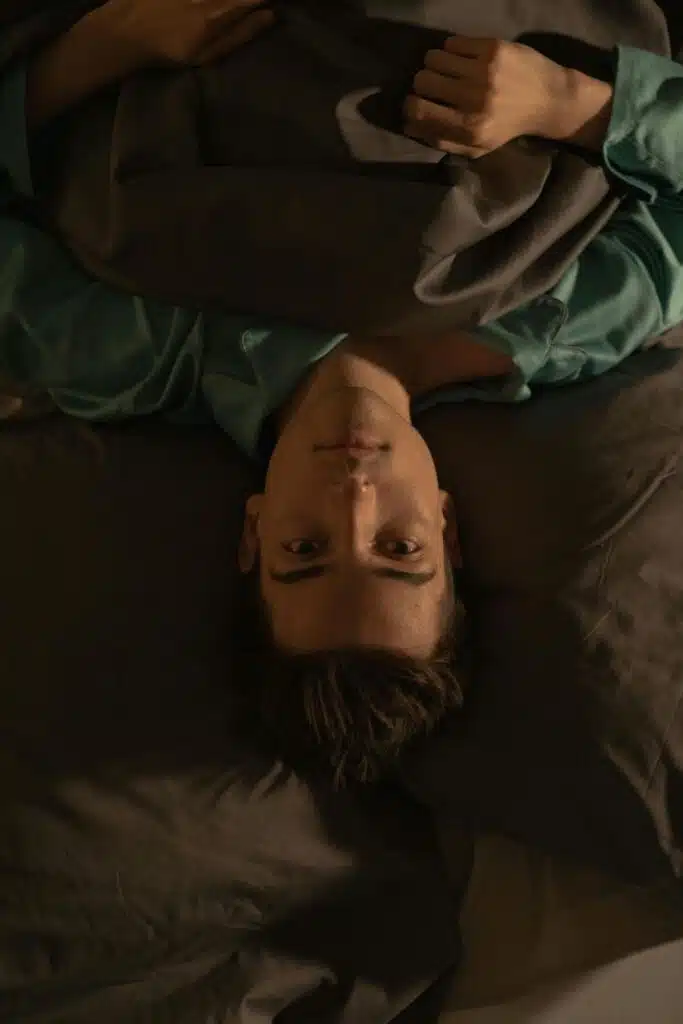

This creates a difficult cycle: rumination contributes to exhaustion and prevents rest and recovery, while exhaustion makes rumination harder to manage and more likely to occur. You might find yourself lying awake at 3 AM, exhausted but unable to stop analyzing something that happened days or weeks ago. Your body desperately needs sleep, but your mind won’t grant permission.

Burnout also tends to lower the threshold for what triggers rumination. Things you might normally be able to brush off or process quickly become sticky, demanding extended mental attention. The cognitive flexibility that allows you to shift between thoughts becomes rigid, and the thoughts that do capture your attention hold on with greater intensity.

Why It’s Different From Typical Overthinking

While everyone ruminates sometimes, autistic rumination has distinct characteristics that set it apart from typical overthinking or worry. Understanding these differences can help both autistic individuals and those who support them recognize what they’re dealing with.

First, it tends to be more persistent and more detailed. Where a neurotypical person might replay a conversation once or twice, an autistic person might replay it dozens or even hundreds of times, each time noticing new details or considering new interpretations.

The thoughts often have a forensic quality—examining evidence, looking for patterns, trying to solve an unsolvable puzzle. There’s a sense of trying to reverse-engineer social interactions or situations to understand the underlying rules or meanings. This isn’t neurotic anxiety (though anxiety may certainly be present)—it’s the autistic brain doing what it does best: analyzing, systematizing, and seeking patterns.

There’s also often a strong need for resolution or understanding. The rumination isn’t just anxiety about what might happen or worry about judgment. It’s an attempt to process, categorize, and make sense of something the brain perceives as incomplete or incomprehensible. The mind feels like it should be able to figure this out, and it won’t rest until it does—except sometimes the puzzle has no solution, or the solution isn’t accessible through analysis alone.

Another key difference is that autistic rumination can be harder to interrupt through willpower or distraction alone. Telling yourself to “just stop thinking about it” is often about as effective as telling yourself to stop being hungry. The thought loops have a quality of automaticity and persistence that resists simple cognitive redirection.

The Hidden Costs

Rumination extracts significant costs that aren’t always visible to others or even fully recognized by the person experiencing it. The mental energy consumed by persistent thought loops is energy that’s not available for other tasks, relationships, or self-care. You might appear to be functioning normally while internally running intensive mental programs that drain your resources.

Sleep disruption is one of the most common and damaging effects. When rumination activates at bedtime, it can delay sleep onset for hours. Even when you do fall asleep, the mental tension may lead to restless, unrefreshing sleep. Chronic sleep deprivation then worsens executive function, emotional regulation, and sensory sensitivity—making you even more vulnerable to rumination.

Autistic rumination can also interfere with being present in current moments. While physically present in a conversation, your mind might still be replaying yesterday’s interaction, analyzing its meaning, and missing what’s happening right now. This can create new social difficulties, which then become new fodder for rumination—another vicious cycle.

Strategies That Can Help

Managing autistic rumination isn’t about forcing your brain to think differently or suppressing thoughts through willpower. It’s about working with your neurology, developing skills and strategies that respect how your mind actually operates.

Scheduled worry time sounds counterintuitive, but some people find success by designating a specific 15-30 minute period each day for rumination. You tell yourself, “I don’t need to figure this out right now; I can think about it during my scheduled time at 7 p.m.” The brain seems more willing to postpone the thoughts when it knows there’s a scheduled opportunity to process them. During the scheduled time, you can write about the concerns, talk them through aloud, or simply allow the rumination to run its course in a contained way.

Pattern recognition as an ally means working with your autistic brain rather than against it. If you can identify the triggers and patterns in your autistic rumination—what situations tend to spark it, what time of day it’s worst, what mental or physical states make you vulnerable—you can sometimes catch the loop before it fully engages. You might notice, “I always ruminate after large social gatherings” and build in recovery time and grounding activities for those occasions.

Body-based practices like deep pressure, rocking, or engaging with a special interest can provide the regulation needed to shift mental gears. Sometimes the body needs to change states before the mind can follow. Weighted blankets, compression clothing, or self-applied pressure can activate the parasympathetic nervous system and create a sense of safety that makes letting go of thoughts feel less threatening.

External processing through writing, talking to a trusted person, or even speaking thoughts aloud to yourself can sometimes help complete the loop that rumination is trying to close. The act of externalizing the thoughts—getting them out of your head and into the world in some form—can provide the sense of completion or acknowledgment that allows the mind to move on. Journaling can be particularly effective because it creates a record that the brain can reference, reducing the feeling that the thoughts will be lost if you stop thinking about them.

Time-boxing is another approach where you allow yourself to ruminate for a specific, limited period—say, 10 minutes—and then deliberately shift to another activity. Setting a timer can help maintain the boundary. This acknowledges the need to process while preventing rumination from consuming unlimited time and energy.

Accepting incompleteness is perhaps the hardest strategy but sometimes the most necessary. Some social interactions will never be fully understood. Some situations won’t have resolution. Some questions don’t have answers that can be found through analysis. Learning to tolerate that uncertainty, to make peace with not knowing, is an ongoing practice that goes against the grain of autistic cognition but can be liberating when achieved.

This doesn’t mean giving up on understanding or stopping your analytical nature. It means recognizing when continued analysis isn’t producing new insights, and choosing to invest your mental energy elsewhere, even though the incomplete feeling remains.

When to Seek Support

If rumination is significantly interfering with sleep, work, relationships, or daily functioning, it may be time to seek professional support. Therapists familiar with autism and cognitive patterns can offer targeted strategies tailored to how your mind actually works, rather than generic advice designed for neurotypical thinking patterns.

Therapists trained in approaches like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) or those with specific experience working with autistic adults may be particularly helpful.

In some cases, rumination may be part of a co-occurring condition like OCD, anxiety disorders, or depression that could benefit from specific treatment, potentially including medication. The line between autistic rumination and OCD-related rumination can be blurry, and professional assessment can help clarify what you’re dealing with and what treatments might help.

A Final Thought

Autistic rumination isn’t a character flaw, a sign of weakness, or something you should be able to simply overcome through positive thinking or willpower. It’s a manifestation of a brain that processes deeply, seeks patterns, and strives for understanding. The same cognitive style that leads to rumination also contributes to the intense focus, attention to detail, thorough analysis, and systematic thinking that characterize autistic cognition.

The goal isn’t to stop thinking deeply or to somehow make your brain less autistic. It’s to develop flexibility in where and how long you direct that powerful attention.

Your mind’s tendency to examine and re-examine isn’t the problem—it’s one of your strengths. The challenge is learning when that examination serves you, helping you solve problems and understand your world, and when it’s time to gently redirect your attention elsewhere.

You deserve mental peace, and that peace doesn’t require you to think differently or be someone you’re not. It requires understanding your own patterns, developing strategies that work with your neurology rather than against it, and being patient with yourself as you learn to navigate the landscape of your own mind.

Sharing Knowledge About Common Autistic Behaviors

There are many behaviors associated with having autism. Keep in mind that everyone presents differently, which is why it is caused by a spectrum disorder. However, there are common autism behaviors. Learn more about them.

- Autism and Eye Rolling: Why It’s Odd, But Perfectly Okay

- Eye Contact Avoidance: 8 Best Ways to See Eye to Eye

- Autism and Poor Hygiene: The Smelly Truth to Overcome

- Autism Self-Diagnosis: It Isn’t Always A Mistake

- 10 Proven Techniques for Managing Autism and Sensory Issues

- Behaving Badly: Is Using Autism as An Excuse Ever Okay?

- Autism and ADHD: Making Sense of the Overlap

- Autism Masking & Code Switching: How to Redefine Acceptance

- Autistic Stimming Behaviors: Why We Do and How It’s Important

- OCD and Autism: Could You Have One Condition or Both?

- Break Free From These 7 Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms

- Autism in Sports: Hyper-Focus Can Be A Commanding Competitive Advantage